IT IS that time of the year when the country’s Finance ministry has the unenviable task of coming up with measures that are meant to drive economic growth, as well as allocate resources for various Government programmes.

And the trickiest part is that there are limits to taxation, but not so much on spending.

The 2024 Budget is vital, because it comes as the Second Republic’s first five-year national development plan — the National Development Strategy 1 (NDS1) (2021 to 2025) — has already passed the halfway stage.

“The 2024 National Budget will seek to scale up domestic resource mobilisation, deepen economic transformation and promote both domestic and foreign investment in support of programmes and projects that will deliver on the NDS1 priorities,” reads part of the 2024 Budget Strategy Paper, which outlines the fiscal strategy that guides wider budget consultations.

Zimbabwe expects to become an upper middle-income economy within the planned period for the National Development Strategy 2 (NDS2) (2025-2030), the successor to NDS1.

In simpler terms, an upper middle-income economy translates to an improvement in the lives of ordinary citizens, especially with regard to the purchasing power of their salaries, what they eat, service delivery and quality of healthcare and education, among other key factors.

It is, therefore, critical that Treasury maintains, or even boosts, funding for NDS 1 programmes.

Prioritising agriculture

With 2023 marking the midpoint in the implementation of NDS 1, Finance and Investment Promotion Minister Professor Mthuli Ncube — while recently announcing outcomes of a Mid-Term Review of the NDS 1 that was carried out between March and June this year — said “progress has been positive across all the 14 priority areas”.

So, the 2024 National Budget will likely prioritise agriculture, given that food and nutrition security is a key pillar of Government’s economic development plan.

The Government plans to reduce food insecurity from 59 percent of the population recorded in 2020 to below 10 percent by the end of the first phase of the NDS1.

One of the key targets in this regard is increasing maize (a key staple food in the country) output to three million tonnes by 2025.

It is, therefore, expected that next year’s financial plan will be predicated on boosting agricultural output through financing of Government’s interventions in the sector.

Service delivery

Efficient service delivery is another key facet of NDS1.

Proper funding of the devolution programme is absolutely critical to achieve inclusive development that leaves no one and no place behind.

With the Constitution stipulating that 5 percent of the budget should be allocated to local authorities, disbursements are likely to be sizeable, given the $47 trillion cap to next year’s budget.

Health and well-being are equally important to Vision 2030.

Increasing health infrastructure and addressing the issue of drug shortages and antiquated equipment have been key goals under NDS1.

So, funding of the health sector should continue to be a priority. Some analysts maintain that the largest chunk of the 2024 Budget should go towards health.

In the 2023 Budget, Treasury allocated $473,8 billion towards the sector, which constituted 11 percent of the $4,5 trillion budget.

Observers say the allocation for the health sector must be benchmarked with the Abuja Declaration, which recommends that 15 percent of the budget should be on health.

Education and housing

Further, an upper middle-income economy requires broad access to quality education.

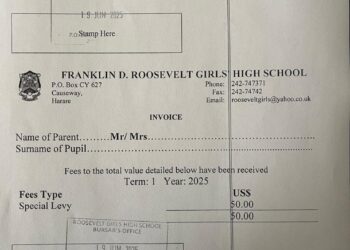

And one of the key targets of the NDS 1 is boosting education infrastructure and the capacity of educational institutions.

It is likely then that the 2024 Budget will prioritise funding the construction of new schools and allocations to the Basic Education Assistance Module.

Government is also focused on improving housing delivery. This means Treasury will continue to finance programmes aimed at reducing the country’s housing deficit.

The housing waiting list presently stands at over 1,5 million.

Revival of the Housing Fund and the National Housing Guarantee Fund is also envisioned under NDS1.

There are also cross-cutting issues such as the youth; the environment; gender; people living with disabilities; and information and communications technology that cannot be ignored.

And beyond funding programmes under the NDS1, there are also numerous interest groups that may or may not advocate larger allocations from the budget.

Businesses and manufacturers, for example, will be on the lookout for measures that boost production and improve the ease of doing business.

And workers will, no doubt, be listening for tax relief measures.

All these and other critical funding requirements should be achieved without exceeding the allowable budget deficit of 2 percent that we have set for ourselves.

According to Professor Ncube, the macro-fiscal framework projects revenue collections next year to reach $44,1 trillion.

But another tricky part of the budgeting process are unexpected expenses.

Cyclone Idai in 2019, the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and droughts in the recent past serve to highlight the damaging effects of unexpected shocks.

It, therefore, behoves Treasury to set aside a contingency fund, as it has always been doing.

Economic growth is forecast to slow down to 3,6 percent next year, from 5,2 percent expected in 2023, largely due to the expected impact of the El Niño weather phenomenon and continued geopolitical tensions.

Source Zimsituation