And I’ll give you a hint about what’s next.

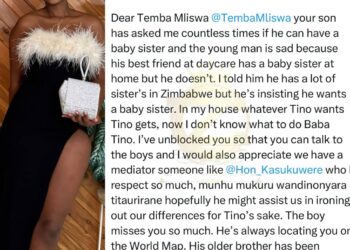

President Joe Biden, looking down, as if contrite.

COVID took Donald Trump out of the White House—then, four years later, COVID put him back in. Shocks from the pandemic produced generational inflation on a global scale that wreaked havoc on incumbents in country after country. Cost-of-living increases made for an economy that most people feel hasn’t worked for them. This was an election in which fundamental indicators pointed to the bums getting booted out. So they were.

Looking at the breadth of Donald Trump’s victory, then, it would be foolish to go too far down any particular rabbit hole of wrong tactical decision made here, inexact position on this issue there. The map wasn’t what it was because Kamala Harris picked Tim Walz instead of Josh Shapiro as her running mate, because she was either too supportive of Israel’s war on Gaza or not supportive enough, or because she spent too much time with Liz Cheney. The environment was the environment, and it’s hard to pin the total blame on any one choice or person.

That said, let’s talk about President Joe Biden.

The country decided years ago that Biden was too infirm to run for a second term. In June 2022, a New York Times poll showed that only 26 percent of Democrats thought he should be renominated, and their top concern was his age and visible decline. The idea that this person—whom the public also disapproved of for a variety of policy reasons—could serve as president until 2029 struck the country as absurd on its face.

Biden and the Democrats took the wrong lesson, though, from the 2022 midterms. Somehow, Democrats’ better-than-expected performance was interpreted in the White House as a vote of confidence in Biden, when he had little to do with it. The Democratic coalition had won over more high-propensity college-educated voters, who always turn out in midterms, while Republicans’ coalition had become more irregular. The Supreme Court had, a few months earlier, taken away a constitutional right from an entire sex to have control over their bodies. Jan. 6 was still fresher in voters’ minds, and Trump had worked diligently to ensure that Republicans nominated conspiratorial yahoos in every meaningful swing election. They didn’t get very far without Trump on the ballot to inspire turnout.

But the party incorrectly took the midterm performance as a sign that Biden should be locked in as the nominee. It would take more than a year and a half, and a shocking, late-in-the-game debate debacle, for Biden and the party to accept that his candidacy was untenable.

Biden endorsed his vice president, and the party rapidly fell in line. This may still have been the right decision at that late point. The campaign apparatus could be swiftly transferred to another member of the ticket, and Harris already had—for better or worse—some experience being battle-tested in the spotlight of national politics.

Your mileage may vary, but I find it difficult to be too upset with Harris. She was thrust into an impossible situation: facing extraordinary headwinds on the economy and the border and inheriting the administration’s unpopularity without having been the decisionmaker. Having to define herself—and avoid being defined by Trump—in 90 days. Remaining loyal to Biden while trying to keep her distance. Having to take the weight of the future of the world on her shoulders. And having to persuade a country that has never elected a Black woman as president, or a woman at all, to elect her. You can’t blame her for a lack of trying.

And yet, her limitations as a politician were exposed, just as they were in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary. She’s too cautious, too poll-driven, too mercenary. There’s too much advice in her head, and no one really knows who she is or what she wants.

These limitations are things that are useful to expose in a yearlong presidential primary. There was some thinking, after the Democrats’ summer-candidate switcheroo, when Harris was riding high, that eschewing a messy primary altogether might be a model for the parties going forward, to the extent they could get away with it. Even if the Democrats’ 2024 circumstances were replicable, which they aren’t, I’d say that argument has been resoundingly rebuked. Harris may not have won a full-year primary against the best candidates the Democratic Party had to offer—or she might have, because she could’ve gotten sharper during that process. Democrats might have gotten sharper during that process.

But that’s a process Democrats didn’t allow themselves to have because, despite a deafening chorus from the public that Biden shouldn’t run for a second term, he did. Biden was certain to lose, and the most that replacing him with Harris atop the ticket did was give Democrats a chance. It was a Hail Mary. Despite what you may be seeing of late, those usually don’t work.

Democrats will spend the next years figuring out what went wrong and how to rebuild. We all eagerly await this tedious process. Want to know a little secret, though? They probably won’t change much, and they may get away with it. Trump will make a mess of himself once he’s back in office, and the (probably) unified Republican Congress will spend capital on slashing Medicaid and cutting taxes for rich people, setting Democrats up for improvement in the midterms. Democrats will have an open primary with star governors in 2028, and Republicans will nominate someone who won’t have that special something Trump has in activating new voters. Since I started covering politics in 2007, I’ve seen the Republican Party declared dead (2008), the Republican Party declared dead (2016, after nominating Trump), the Democratic Party declared dead (2016, after Trump won), the Republican Party declared dead (2020), and now the Democratic Party declared dead (2024). Maybe this one will last. Probably not.

But Democrats would do well to nominate someone who’s capable of serving for eight years. And watch out for those pandemic-induced supply shocks.