Zimbabweans vote next week in an election many hope could end the country’s lengthy economic crisis, but those expectations are tempered by concerns that the contest is skewed in favour of a party that has been in power for more than four decades.

Mineral-rich Zimbabwe was once considered one of Africa’s prosperous economies, but it has been in economic turmoil since 2000 when former leader Robert Mugabe led the violent seizure of white-owned farms to resettle landless Blacks.

Mugabe was ousted in a 2017 military coup after 37 years in power and replaced by his long-time ally President Emmerson Mnangagwa, but the economic turnaround many hoped for at that time has proved elusive.

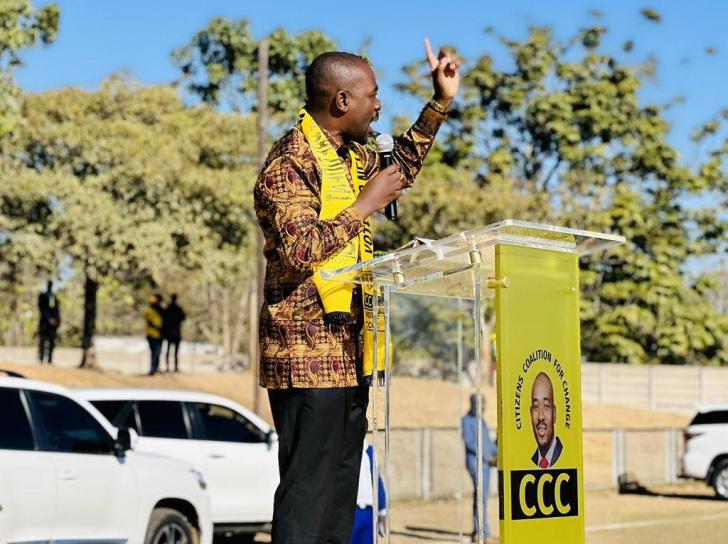

There are 11 candidates running for president in Wednesday’s vote, but the real battle is between 80-year old Mnangagwa and Nelson Chamisa, a 45-year old lawyer and pastor who leads the opposition Citizens’ Coalition for Change (CCC). The election is also for lawmakers and local council leaders.

Mnangagwa’s 2018 election win was unsuccessfully challenged by the opposition and political analysts say the country could be headed for a repeat of that. The ruling ZANU-PF denies opposition allegations that the playing field is not level.

“Of course, we are headed for another disputed election,” said political analyst Pedzisai Ruhanya, referring to a dispute over the voters roll as one contentious issue.

The CCC has taken the electoral commission to court to demand access to electronic copies of the voters roll so that it can be searched and analysed.

The electoral commission has said it has given all parties printed copies of the roll. The courts have yet to rule on the CCC application in the case, which is one of several court challenges mounted by the opposition ahead of the vote.

There have also been reports of voter intimidation, especially in rural areas of the country of 15 million people, voter watchdog Electoral Resource Centre (ERC) said.

“General public sentiment, as noted in several surveys, reveals that people have very little confidence in the electoral process as well as the election management body in the country,” ERC said in a statement on Monday.

Police have blocked some of the opposition’s rallies but have denied accusations that they have targeted only opposition campaigns, saying rallies for both major parties have been stopped on grounds of public safety.

The opposition also says its supporters are routinely arrested under Zimbabwe’s tough public order laws, and that there have been cases of violent intimidation of its activists by ZANU-PF supporters.

“The odds are many. We’ve also seen a number of our supporters being intimidated and harassed, but citizens remain defiant. People are ready and mobilised for change,” CCC spokesperson Fadzayi Mahere told reporters on Wednesday.

ZANU-PF says it is not favoured by the courts, police or public media. At a news conference on Thursday, ZANU-PF spokesperson Chris Mutsvangwa denied allegations of voter intimidation and unfair electoral processes.

He accused the opposition of being “obsessed with criticising the electoral process so that they have something to say after losing”.

‘BAD’ HUMAN RIGHTS

Wilbert Mandinde, an official at the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum, said the human rights situation “has been bad” during the campaign.

“We believe that it is not proper for members of the opposition to have to struggle to gather, to have to struggle to campaign,” said Mandinde.

Mnangagwa narrowly defeated Chamisa in the 2018 election, which the opposition disputed over alleged irregularities. The president’s victory was upheld by the Constitutional Court.

The opposition is hoping it can defy the odds and win this time, riding on frustrations over the longrunning economic crisis.

Political analysts say young voters who have never known a prosperous Zimbabwe could play a significant role in the election. One-sixth of the registered electorate are first-time voters.

Source NewZimbabwe