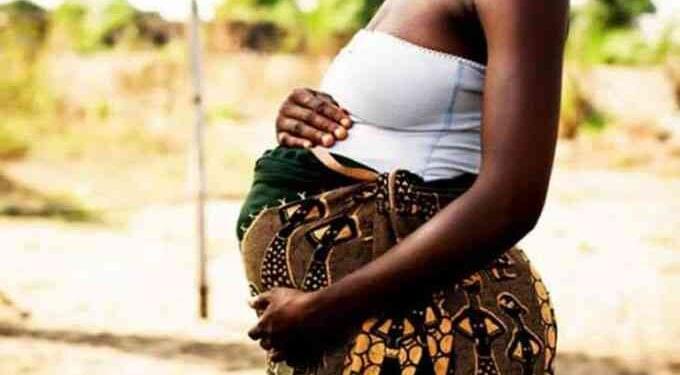

AFTER being forced out of the family house in January this year when she fell pregnant and was coerced into marriage by her parents, Ruvimbo (14) found herself leading a life of misery alone in a rented room in the “Makomboni” area of Epworth, south-east of Harare.

“This happened in the first month of my Grade 7 at Makomo Primary School in the same area,” she said, with the pregnancy now showing.

Since birth, Ruvimbo has lived with her parents in their one-room lodgings in Chiremba area, which is quite normal in her area. She is the only child.

Ruvimbo says her life went into disarray when she fell pregnant after sleeping with a boy almost her age.

She was not prepared for the next stage of her life.

Unbeknown to her, the pregnancy would result in her parents forcing her out of the house.

Her equally young boyfriend, who was under the custody of his parents, refused to own up. His parents also refused to take responsibility for their son’s actions insisting that he was too young to be a father.

Ruvimbo was broken. She found herself alone with no one to take care of her.

Keep Reading

Breaking the stigma: Zimbabwe’s teenage mothers speak out (Part 2)

“Ever since my parents forced me out of the house, I have been struggling to survive,” she says.

“On many occasions, I would sleep on an empty stomach. It pains me because I know my parents are there, but they are not willing to help me.”

This is the second part of a three-part series: Breaking the stigma: Zimbabwe’s teenage mothers speak out about family abandonment and societal challenges; in which teen mothers in Zimbabwe, who has fallen victim to societal norms and beliefs share their stories.

In African society, falling pregnant under the age of 18 is considered a “taboo“ and often see young girls being stigmatised by society. Girls are considered to be at fault irrespective of whether the pregnancy was a mistake or a result of abuse.

In an interview, Compass Zimbabwe project lead (Pangea Zimbabwe Aids Trust (PZAT), Munyaradzi Chimwara said Zimbabwe’s cultural beliefs and societal norms forced girls to elope once they fall pregnant. This leaves them vulnerable and exposed to poor living conditions, which can lead to their further exploitation due to a lack of protection from their parents and the law.

“The biggest challenge in this country is that we have gone into a season of sexual debut among young people, and as parents we are in denial to accept the reality. That is why as Compass, we have been pushing for a Bill in Parliament that allows children below the age of 18 to have access to Sexual Reproductive Health products (SRHp),” he said.

“Preventing young girls from having access to SRHp can, one, create a population of young mothers; (two), create a burden of illegal abortions as well as create a burden for parents to take care of their children and grandchildren at the same time.”

Although every child has rights as set out in section 81 of Zimbabwe’s Constitution, amendment of section 2 of Chapter 5:06 (q), a child who is pregnant (below 18 years) needs care.

However, due to poor implementation of the law, many young mothers have fallen victim to abandonment by care-givers and the government as well.

Armed with such evidence, PZAT through “Shaping Adolescents and Young Adults in Zimbabwe” (SHAZ) lobbied for access to sexual reproductive health products for adolescents to prevent unwanted teen pregnancies.

“As an organisation we believe that this urgently need to be addressed using the lenses of the era that we are living in, where the law on one side is saying something else, while cultural norms and beliefs on the other side are saying another thing with the children at the centre behave independently,” Chimwara said.

No law against child marriages

Currently, Zimbabwe has no law that criminalises child marriage and this has promoted sexual abuse and exploitation of young girls. Most of the men who impregnate teenagers decline responsibility for the pregnancies.

Home Affairs and Cultural Heritage minister Kazembe Kazembe confirmed this circumstance but refused to comment saying: “In Zimbabwe we have nothing called child marriage.

“My department has nothing to say about child marriage in Zimbabwe because it is not a criminal offence. We have no law on child marriages now.”

Without laws which criminalise the sexual exploitation of children, cases of child pregnancies have escalated over the past years.

Statistics from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) showed that about 350 000 girls between the ages of 10 and 19 fell pregnant between 2019 and 2022 in Zimbabwe.

According to the recently released National Assessment on Adolescent Pregnancies in Zimbabwe survey report that was conducted by the Health and Child Care ministry in conjunction with Unicef and Unesco, more than 4 000 girls aged between 10 and 14 years, fell pregnant and were booked to deliver at health institutions countrywide between 2019 and 2021.

The survey also found that 2021 had the highest number of pregnant adolescent girls aged from 10 to 14 years.

An increasing number of pregnant adolescent girls tested positive for HIV upon booking at antenatal clinics.

The report attributed the increasing incidence of pregnancy among adolescents to closure of schools and the reported increase in domestic violence due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thirty percent of adolescent girls were found to be sexually active, while approximately 31% (134) reported having had forced intercourse in their first sexual encounter, and around 75% (315) said their first sexual encounter was with boyfriends.

Only 23% (97) was with husbands, 1,5% (10) with strangers, 0,8% (6) with relatives and 0,1% (2) with casual partners.

Lana (15), who is also pregnant was left hopeless when a court asked her to bring a paternity test after her mother filed a case of rape. The case was heard at Epworth Magistrates Courts in May this year.

Lana says she was sexually exploited by her boyfriend’s friend in January this year without protection and in February, her boyfriend also had unprotected sex with her leading to confusion as to who was responsible for the pregnancy.

“On this day, l met my boyfriend’s friend on my way to the shops. He told me that he also was on his way to the shops but wanted to pass through his house to pick up something. He asked if I could accompany him and I agreed since both of us were heading to the shops,” Lana said.

When they got to his house, he asked her to get inside and wait for him to fetch something.

“To my surprise when I got into his house he locked the door and asked if we could have sex. At first, I refused but he was adamant that he was not going to open the door until I gave in.

From there she never met him again and in February this year, she was intimate with her boyfriend.

Later she discovered that she was pregnant but she does not know by whom.

“My mother was forcing me to elope but both men are refusing responsibility,” she said.

With no one on her side, Lana decided to report the case to the police. Her boyfriend and his friend were both arrested, but the court said paternity tests should be carried out to determine the father of the child before further proceedings.

The two suspects were released on bail.

“What pains me most is that these guys are now making a joke of me saying that I am cheap,” said Lana with a broken voice.

The surge in child pregnancies in Zimbabwe, according to the UNFPA has seen about 3 000 girls dropping out of school in 2019.

“In 2020 the number of school dropouts due to teen pregnancies rose to 4 770, and 5 000 in 2021,” the organisation said.

Felicia (17), a single mother to a four-month-old baby is back in with her mother after she was physically abused by her husband.

Due to peer pressure, Felicia dated a 24-year-old man from her neighbourhood.

“With my boyfriend, we used to be intimate whenever we felt like, with or without protection and when I realised that I was pregnant we decided that I should move in with him,” she said.

Felicia’s husband paid a bride prize in-line with the African custom.

“We stayed together for a few months, but things changed when he started abusing me,” said Felicia with tears rolling down her cheeks.

She would be forced to sleep outside on an empty stomach, but one day her husband turned into a beast.

“On this day my husband brought his new girlfriend home. When I asked about it, he grabbed me by the throat and started beating me up,” said Felicia adding;

“I thought that I was going to die.

“I was saved by the neighbours who then told my mother the situation that I was living in as they feared that my life was in danger.”

Felicia had hidden the abuse from her mother for a long time fearing that she would not accept her back home.

Felicia’s mother, Faustina Dube, however, welcomed her back with both hands.

“Ndakati mwana wangu ngaadzoke, because unourairwa mwana”, (Fearing that she might be killed, I decided to take my daughter back). I know that my child was impregnated while in school and what pains me the most is that she was so bright and she had to drop out of school,” said Dube.

Dube said she was initially bitter with her daughter but had now accepted the mistake she made.

Due to pregnancy, many girls fail to proceed with their education, compromising their future in the process.

Felicia is a first-born in a family of three. Her father died when she was very young.

“Now that I am back at my mother’s despite having to face societal stigma, sometimes labelled “vekumitiswa” (those who were impregnated), I have also joined the RhoNaFlo family an organisation that provides maternity support to young mothers in my area,” she said.

For Chipo Tsitsi Mlambo, founder and director of RhoNaFlo Foundation, helping teen mothers is something personal to her.

“I lost my mother when she was giving birth to my brother. I was a teenager. The pain could not easily go away, I had to do something that I felt was therapeutic to me”, said Mlambo.

Under the banner: RhoNaFlo Foundation, Mlambo has been providing maternal health support to young mothers. She recently introduced a therapeutic intervention.

“I spent more time with teen mothers; I realised that their problems are a multi-layer of abuse. There have no safety nets, the perpetrators live with them in the same community; family abandonment and societal stigma — It is just too much. According to our Shona culture, first mothers should give birth under the care of their mothers but young mothers in Epworth are living alone with no financial support, mentally and even socially,” said Mlambo.

They introduced an art therapy that focuses on making teen mothers relax, pouring their dreams on a canvas board.

Hermit Myambo of Hermit Art, one of the artists who has been working with young mothers through the art therapy sessions, said art had a way of making people relax.

“Art gives people hope as they can speak their dreams through paint and canvas and I believe that this is the kind of hope that the teen mothers need to help them relive their dreams,” Myambo said.

Ruvimbo, who participated in one of the art therapies, of “what you aspire to be” confirmed that therapy was relaxing and could make her forget her worries for a moment.

“When I was growing up, I always dreamt of becoming a flight attendant, having an opportunity to visit the world and see different people and places.

“Today, I got an opportunity to relive that as I managed to draw an aeroplane as part of my dreams,” she said.

Find out in the final part of Breaking the Stigma: Zimbabwe’s Teenage Mothers Speak Out About Family Abandonment and Societal Challenges how young mothers are working hard to change their ill-fated situations.

Source News Day